This blogpost was originally released through the Good Data Institute (GDI), where I work as a Fellow to to give not-for-profits access to data analytics support & tools for social and environmental good. If you’d like to learn more about GDI, check their website here.

If you are arrested in the U.S. today, COMPAS or an algorithm like it will likely influence if, when and how you walk free. ‘Ethics for Power Algorithms’ by Abe Gong (Medium)

In the previous part of this series, I argued that the productionisation of AI/ML has and will continue to amplify unfairness and societal bias. In short, societal bias refers to the conglomeration of non-statistical social structures that have historically harmed underrepresented demographic groups. This type of bias makes fair decision-making by an algorithm more difficult or even impossible. For example, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Jim Crow laws unfairly oppressed African-Americans in the Southern United States. In turn, these laws would have induced statistical bias since more data about African-American ‘offenders’ would have been collected.

The cost of deploying AI/ML algorithms into production is ever decreasing due to technological advances in hardware, as well as the appearance of cloud services such as Amazon Web Services or Microsoft Azure (decreasing the cost of storage and compute). This, along with the revolution in generative AI that we are currently experiencing (e.g., ChatGPT), will enable many practitioners to get AI/ML algorithms out into the world in a ‘deploy first, ask questions later’ fashion. That is, not understanding the societal impacts and as a consequence of this, we will see biased AI/ML products being deployed at an ever growing rate.

To mitigate these risks, we must program a sense of fairness into these AI/ML algorithms. However, for data practitioners, that is no easy task because fairness is a sociological and ethical concept that often lies outside their comfort zone of technology and mathematical optimisation. For example, in 2017 Amazon scrapped a ‘secret’ AI/ML recruiting tool that favoured hiring males. Because the training data was composed of recruitment information from a male-dominant industry (IT), the algorithm ‘learned’ that males were more preferable for IT roles.

In this post, I’ll provide a quick walkthrough on algorithmic fairness: outlining some existing definitions from this field and discussing why developing a golden standard for algorithmic fairness is so complicated. To illustrate this discussion, I will design a simplified version of a recidivism AI/ML algorithm. This type of algorithm is used to predict the likelihood that an ex-convict will re-offend. In turn, this prediction can be used to inform the passing of a sentence or setting the conditions of parole.

If you’d like to learn how GDI has partnered with the non-for-profit Brother 2 Another to decrease recidivism using a different approach (from the one discussed in this article), read this blogpost here.

Just Enough ML

Getting from data to prediction involves many moving & inter-twinned components. As a result, AI/ML products will be complex and dynamic constructs. Dealing with this complexity has led practitioners to develop patterns such as the ‘AI/ML Product Lifecycle’. In this section, I’ll give an example of an AI/ML algorithm and illustrate each component of its lifecycle.

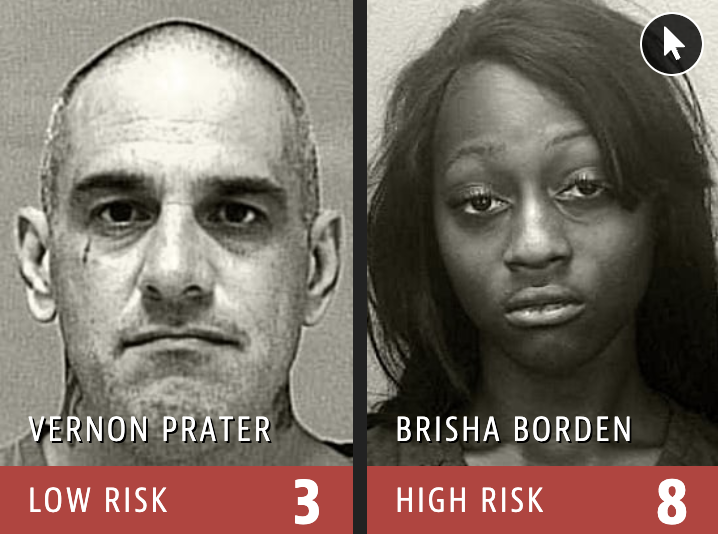

Imagine we would like to build a classifier that will label ex-convicts as low- or high-risk to be re-arrested within some years from release based on a set of attributes (e.g., how much they earn, in what district they live, whether they went to university or where they went to school). This classifier algorithm is a simplified version of the controversial COMPAS recidivism algorithm, which we discussed in the previous post. In short, this algorithm labels ex-convicts as high-risk or low-risk based on the algorithm’s estimated likelihood that these ex-convicts will reoffend within some time (e.g., two years) as we can see in the image below.

For example, following the ‘AI/ML Product Lifecycle’ diagram above, each step would look like the following with our recidivism example:

Data Collection & Data Preparation: We curate a dataset representative of the problem we’re trying to solve. In the case of a recidivism algorithm like COMPAS, this might include gathering anonymised features about ex-convicts that both reoffended and didn’t reoffend within two years from release. Next, we’d have to clean up the data so it has no missing or erroneous values. This step typically requires first an Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA), where we investigate our dataset’s main characteristics and distribution.

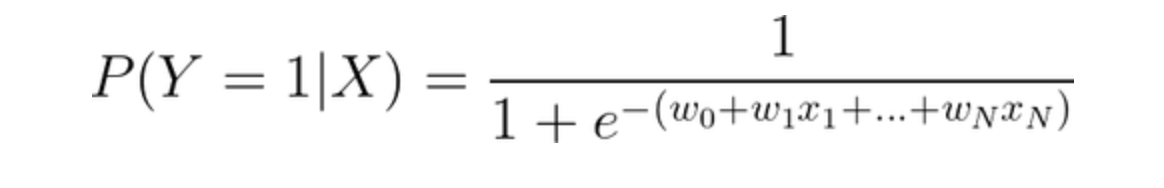

Model Selection: Once we’ve gathered, cleaned and understood our data, we will have to choose an ML model into which we can feed our data. The problem we’re trying to solve will often constrain the models we should select. Since our example is classifying individuals based on some attributes, we will choose the logistic model (or logit model) as it’s the canonical model for this classification problem, given by the following formula (where Y=1 is a high-risk label, the x’s represent attributes from the datasets, and w’s act as weights to prioritise attributes):

Feature Engineering: This technique refers to designing ways of extracting features from the dataset. Feature engineering can take many forms, but for example, a transformation of the data (e.g., a z-transformation) might improve the performance of our model. Feature engineering can also be applied after model validation to improve our model’s performance. While improving a model’s performance can also be achieved for example by enhancing our training data or even choosing a different model altogether, feature engineering tends to be the best strategy we can choose.

Model Training & Tuning: In this step, we split our data into training and test data. With the training data, the model learns the most optimal choice of weights (w’s in the formula above) that minimises the error. For example, attributes of the dataset such as criminal history or age might predict likelihood of recividism better than others. In this step, we can also tune the model’s hyperparameters to improve its performance, which mainly consists of tweaking the model parameters that are not optimised by the model (e.g., learning rate or the model’s initial parameters).

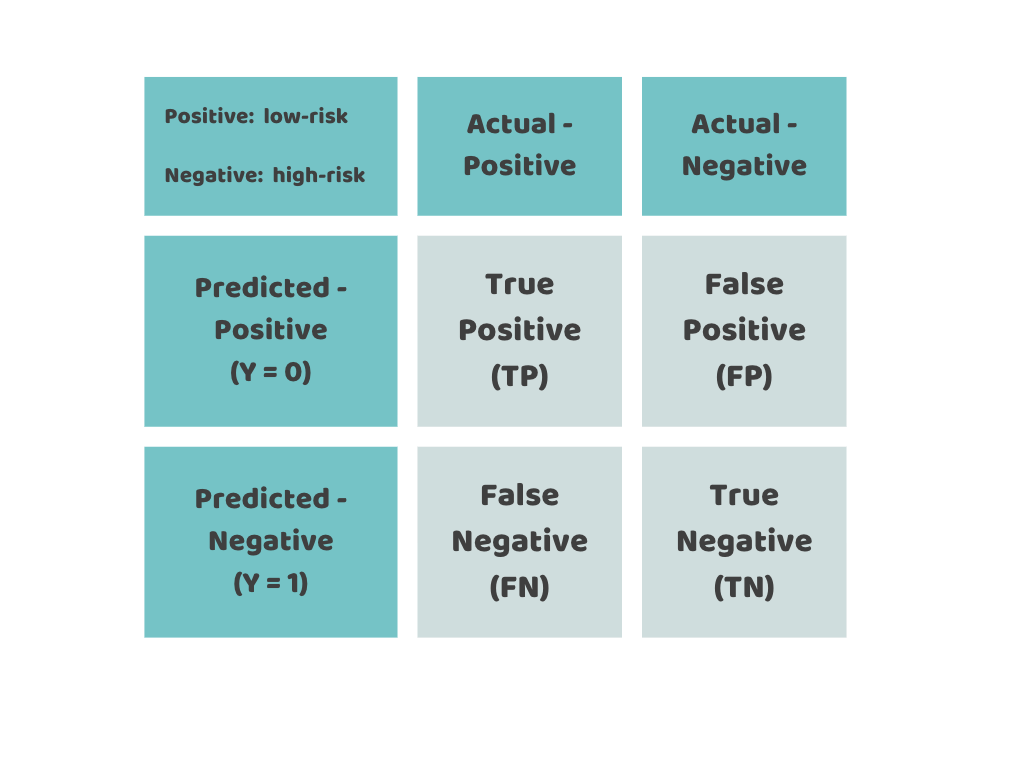

- Model Evaluation: Once we have trained the model, we will feed it the test data to evaluate how it’s likely to perform with data it has never seen. Evaluation of the model will typically involve setting one or more acceptance criteria thresholds. If the model doesn’t meet those thresholds, we will go back and fine-tune the model to increase its performance. The evaluation process will depend on the problem we’re solving and the model we chose. In the case of a classification problem (like our example), we will use the confusion matrix (shown in the figure above) as the foundation for our model validation. In other words, for our logistic model, we need to consider four possible prediction outcomes when we feed each test data record. More generally, each of these belongs to either the positive or negative class, which in our example corresponds to low- or high-risk labels of recidivism respectively:

True Positive (TP): The model correctly labelled an ex-convict as high-risk who actually reoffended within two years from release.

True Negative (TN): The model correctly labelled an ex-convict as low-risk who had not reoffended within two years from release.

False Positive (FP): The model incorrectly labelled an ex-convict as high-risk when actually they hadn’t reoffended within two years from release.

False Negative (FN): The model incorrectly labelled an ex-convict as low-risk when in fact, they did reoffend within two years from release within two years from release.

Once we have these four scenarios, we can combine them to define validation metrics. For example, the most widely-used metric is accuracy, given by Acc = (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FN+FP). We will come back to these metrics in more detail in the next section, as this step is the most important of the ‘AI/ML Product Lifecycle’ for algorithmic fairness.

Note that this is a static and simplified version of a realistic scenario. To fully operationalise the model, we’d also need a deployment strategy, monitoring, continuous training and other CI/CD practices in place. Addressing these challenges (and more) has led to the emergence of MLOps, which is outside the scope of this post (you can read more about MLOps here).

Defining Algorithmic Fairness

Different biases can emerge from different phases of the AI/ML product lifecycle. I recommend reading this blog post to learn more about the ‘how’. Because AI/ML algorithms are susceptible to bias in most components of their AI/ML product lifecycle, the development of ‘fair’ AI/ML algorithms typically becomes a difficult task.

‘Fair Machine Learning’ (Fair ML or FML for short) has emerged as the active field of research that aims to define fairness in ML algorithms technically. Generally, these definitions will require a performance metric to be the same across demographic groups.

To illustrate some of these definitions, we will build on our recidivism algorithm above. In the last section, we learnt that before deploying our model, we would test its performance against some validation metrics.

Although accuracy is frequently the only metric ML and data practitioners use, many have criticised it as an imprecise and vague metric (see this thread for more info). For example, it does not tell us how good the model is at misclassifying records into the positive or negative class. Luckily, more combinations of the confusion matrix will give us further metrics. Some examples include:

Precision (or Positive Predictive Value - PPV): Fairly popular metric that measures the positive predictive power of the model given by the following formula: PPV = TP/(TP+FP). For our recidivism example, this translates to measuring how well the algorithm is at correctly labelling ex-convicts as low-risk.

False Positive Rate (FPR): Fraction of misclassified positives (low-risk) out of all actual negative cases given by FPR = FP/(FP+TN). In other words, this would correspond to the fraction of records misclassified as low-risk out of all the actual high-risk individuals.

False Negative Rate (FNR): Fraction of misclassified negatives (high-risk) out of all actual positive cases: FNR = FN/(FN+TP). In our example, FNR would measure the fraction of misclassified high-risk individuals out of all actual low-risk cases.

Because most definitions of algorithmic fairness require one or more performance metrics to be the same across different groups, we will inevitably get many definitions of algorithmic fairness. As we discuss in the next section, all these definitions make developing a golden standard for algorithmic fairness difficult or even impossible.

Fairness through Unawareness

For the sake of simplicity and to follow other articles discussing COMPAS, imagine we have two demographic groups A and B, representing black and white ex-convicts respectively. One of the earliest definitions of algorithmic fairness is Fairness through Unawareness. This definition is satisfied when no sensitive attribute (race, gender, age, or disability) is used in the algorithm’s decision-making process. For our recidivism example, this would be satisfied if we removed all sensitive attributes from the training data (e.g., age or race) and our model satisfied the following formula: P(A, X_A) = P(B, X_B) if X_A = X_B. However, as we’ll learn in the next section, this definition has severe limitations.

Statistical Parity

More generally, algorithmic definitions of fairness can be classified based on what outcomes they focus on: predicted or actual [1]. Definitions based on predicted outcome are the most naive and intuitive notions of fairness. An example belonging to this class is Statistical Parity. This definition requires the probability to be assigned to the positive class to be the same for both A and B, which would be given by (TP+FP)/(TP+FP+FN+TN). For our algorithm, this would be satisfied if the algorithm would be as good at labelling black ex-convicts as low-risk as labelling white ex-convicts as low-risk, regardless if the prediction was correct. However, the limitation of this type of definition is that it only focuses on what the algorithm predicted rather than on whether it got the predictions right or wrong.

Predictive Equality

The limitation of statistical parity is covered by fairness definitions that consider actual outcome. An example is Predictive Equality, which is satisfied when both groups have the same False Negative Rate, i.e., FPR(A) = FPR(B). In the case of our COMPAS-like algorithm above, this would be satisfied if the fraction of high-risk individuals who were misclassified as low-risk is the same for both black and white ex-convicts.

Equalised Odds

Equalised Odds is an extension of Predictive Equality that also requires the False Negative Rate to be the same across both groups: FPR(A) = FPR(B) & FNR(A) = FNR(B). In addition to FPR, in our example, this would be satisfied if the fraction of ex-convicts who were misclassified as high-risk when they were actually low-risk would be the same for both black and white individuals. This is a great definition of fairness that allows us to measure how poor a model is at misclassifying models, and what the disparities are across groups. However, as we’ll learn in the next section, Equalised Odds still has some limitations that are intrinsic to Fair ML.

Challenges & Opportunities

Many challenges lie ahead to leverage algorithmic fairness, and Fair ML does not fall short of these challenges. For example, studies have shown that algorithms can satisfy some definitions of fairness while violating others [2]. However, this is not so much a constraint of the field of Fair ML but rather a challenge to the application of Fair ML into different real-world domains. In other words, in some applications e.g., the legal system, some definitions of algorithmic fairness will be more suitable than others, but this might be different for instance in the health care system.

Moreover, most (if not all) of the examples of fairness definitions above have limitations. For instance, Fairness through Unawareness is a naive definition of fairness because of proxies, which are non-sensitive attributes that correlate with sensitive attributes. The most notable examples include annual income and education history, which most often (especially in the United States) will correlate to race and socio-economic status. Proxies like annual income or education history are apparent, so they can be spotted and removed from train and test datasets. Unfortunately, other more insidious proxies like postcode, online browsing and purchasing history make it extremely difficult (or even impossible) to remove all sensitive proxies from the algorithm’s decision-making process.

In the case of Predictive Equality, we are making the implicit assumption that FPR is more fair than FNR. However, is that a reasonable assumption? From a fairness perspective, I’d argue that FNR captures fairness better than FPR because FNR measures the fraction of individuals who were misclassified as high-risk when in fact they were low-risk (and could potentially lead to them going to jail unfairly or getting an unfair parole). Nonetheless, from a civic safety point of view, one might argue that FPR is more important as you wouldn’t want to misclassify individuals as low-risk when they are very likely to reoffend.

To remediate this, we could follow the pattern in Equalised Odds and keep requiring more performance metrics to be equal across groups to obtain a golden standard for algorithmic fairness. However, some of these performance metrics are incompatible with each other, and thus, so will be some definitions of fairness too. For example, as pointed out by Chouldechova in her ‘The Frontiers of Fairness in Machine Learning’ paper:

except trivial settings, it is impossible to equalise FPR, FNR and PPV [(precision)] across protected groups simultaneously. [3]

Even if we had a golden standard definition of algorithmic fairness, Fair ML has more fundamental limitations because of its statistical approach. That is, none of these definitions of fairness will guarantee fairness to anyone as an individual. Instead, Fair ML can only offer fairness to the ‘average’ member of the under-represented demographic group.

Because of the landscape of fairness definitions that Fair ML offers, deciding what fairness definition is best suited will depend a lot on the problem domain. This presents an opportunity for data practitioners to collaborate and learn from domain experts. In our recidivism example, working with criminologists will be crucial to developing a fair AI/ML algorithm, as criminologists have conducted criminal justice assessments since the 1920s [4]. For example, evidence seems to suggest that males are more inclined towards violent crime than females (read this criminology article for more information).

In summary, society cannot wholly rely only on technical definitions of algorithmic fairness, and ML Engineers cannot reinvent the wheel and establish what fairness represents across different domains.

Closing Thoughts

This post has introduced Fair ML, an active field of research that aims to define and measure fairness in algorithms technically. This field holds great promise as it can provide data and AI/ML practitioners with systematic tools for measuring unfairness aimed at mitigating algorithmic bias. These tools can be essential not only for data practitioners but for stakeholders and society as whole in a world of ever-expanding biased AI/ML algorithms for decision-making. Unfortunately, this field has some limitations, some of which we discussed in this post. Mainly, although there are at least 20 definitions of algorithmic fairness in the literature, most of these definitions have shortcomings. Moreover, studies have shown that some of these definitions are incompatible.

Ideally, I’d personally like to see a golden standard with an agreed definition of algorithmic fairness. Then, AI/ML products would have to pass rigorous tests to be certified as algorithmically fair, similar to organic and cruelty-free products. However, I don’t see this happening anytime soon (if at all) because of the limitations of Fair ML as well as the overall complexity of this techno- and sociological topic. Realistically, organisations need to pick up one definition of fairness that aligns with their values and stick to it, making that explicit as well as making themselves accountable if they fail to follow this definition of fairness, as discussed in the previous post of this series.

in the end, it will fall to stakeholders – not criminologists, not statisticians and not computer scientists – to determine the tradeoffs […]. These are matters of values and law, and ultimately, the political process. [4]

Algorithms cannot be the only resource for decision making. In a best-case scenario (when they are not biased), these algorithms can provide a prediction probability. ML Engineers cannot or should not be the only contributors that will champion this space. This, however, presents an opportunity for ML practitioners and stakeholders to embrace the interdisciplinary nature of Fair ML and work with problem-domain experts. In our example of the recidivism algorithm, it’d be foolish not to work with criminologists to build the algorithm as they have conducted criminal justice assessments since the 1920s [4].

Finally, it is essential to acknowledge and respect the ‘hierarchy of risks’ when it comes to deployment and roll-out of AI/ML technology. For example, misclassifying ex-convicts as high-risk has more detrimental implications for their human welfare than misclassifying what movie they’re likely to enjoy. Likewise, misclassifying a person as not fit for a particular job role has more damaging implications to that person and their career than misclassifying what next product they’re most likely to buy online. AI/ML algorithms used for decision-making are in their very infancy, so whatever breakthrough or insight we might come across, we must put it under scrutiny and work iteratively.

Academic References

[1] Mitchell, S., Potash, E., Barocas, S., D’Amour, A., & Lum, K. (2018). Prediction-Based Decisions and Fairness: A Catalogue of Choices, Assumptions, and Definitions. arXiv e-prints. https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.07867

[2] Chouldechova, A. (2016). Fair prediction with disparate impact: A study of bias in recidivism prediction instruments. arXiv e-prints. https://arxiv.org/abs/1610.07524

[3] Chouldechova, A., Roth, A. (2018). The Frontiers of Fairness in Machine Learning. arXiv e-prints. https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.08810

[4] Berk, R., Heidari, H., Jabbari, S., Kearns, M., & Roth, A. (2021). Fairness in Criminal Justice Risk Assessments: The State of the Art. Sociological Methods & Research, 50(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124118782533